One of the more interesting things about facilitation is that you have to be prepared for just about anything. Retrospectives and exploratory sessions can generate very strong emotional responses – from yelling, to crying, to utter silence. However, most retrospectives are about improvement – part of the kaizen philosophy. At the end of the day, the group expresses their emotions, we find things within their scope of power they can act on to change, and the group gets a little better. However, the outcome isn’t always about improvement – sometimes it can be about dissolution.

One of the more interesting things about facilitation is that you have to be prepared for just about anything. Retrospectives and exploratory sessions can generate very strong emotional responses – from yelling, to crying, to utter silence. However, most retrospectives are about improvement – part of the kaizen philosophy. At the end of the day, the group expresses their emotions, we find things within their scope of power they can act on to change, and the group gets a little better. However, the outcome isn’t always about improvement – sometimes it can be about dissolution.

A couple of months ago I was asked to facilitate a discussion for a local church’s council members. After nearly 12 years of work, they had come to the point where it was time to close their doors from an emotional, personal and financial perspective. As you can imagine, a church has a strong emotional bond for its members – especially those who spent many years of their life building it up. Over the course of several hours we were able to move the council through an objective look at their current state while honoring the necessary subjective and emotional content they felt the need to express. By the end, with the group literally in tears, they had all agreed on a course of action.

When dealing with these kinds of emotional situations as a facilitator, there are some steps you can do to help make things go smoother:

- Take Control – This is key no matter what you are facilitating, but especially true in high-emotion situations. You need to be able to focus and direct conversations. In this session, both the existing pastor and the council president initially stayed standing with me in the front of the room. I “allowed†it – until they couldn’t control their need to jump into the conversation and answer questions, at which point I asked them both to sit down

- Understand the situation – I’ve had some experience with building churches, and with the challenges this particular group faced. This isn’t about being an expert, but instead about being able to empathize and predict where the conversation is going

- Understand the grief process – When a facilitation involves end scenarios – closing of a business, shutting down of a team, talking about death – you should be prepared for working through a grieving process. While the grieving process is talked about to be in stages – denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance – it can be much more complicated. In this scenario it meant that I had to be prepared for the group to outright reject the discoveries they were making – and then to be angry with them, then to bargain through them until we got to acceptance. Amazingly, I saw very clear delineations throughout the session:

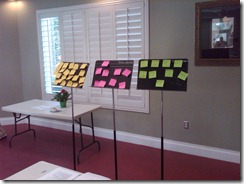

- Denial – This stage is interesting in that emotional reactions can lead people to reject outright facts in front of them. One key to getting through denial is gently keeping the information in front of them. The picture above is from the facilitation session – the yellow stickies were all of the group-identified challenges, compared to the greens which were the positives they had. This helped keep the group reminded that we weren’t meeting because they thought there was a problem – there was a problem.

- Anger – Once the true facts of their situation came to light, there was a lot of anger. This was generally expressed in the form of blame – blame towards each other, towards the church body, towards other groups that were involved. The key here is to allow the expression of anger without allowing it to devolve into personal attacks. One particular challenge was that people who were still in the denial phase felt they needed to “defend against the attacksâ€.

- Bargaining – As the group began to accept where they were, the bargaining started in. “Maybe we can just make it through Christmas.†“We could sell X, Y and Z, and have each of us contribute $10,000.†While this kind of exploration is healthy – and perhaps vital at an earlier stage – it’s important to recognize that the group needs to move through this, and as a facilitator keeping back to the facts the group developed will help this.

- Stay Calm – When emotions are running high, anything is bound to happen. I’ve had people walk out of emotional retrospectives, yell and scream, and seen physical outbursts. One of your most important jobs is to maintain a safe environment. This does not mean shutting down all outbursts, since different groups may have different cultural norms. Instead, carefully watch the other participants to see if they are pulling back, and ask others to hold their expressions – or to leave, if necessary.

- Allow the group to decide – As a third-party not caught up in the emotional aspect you may feel the need to point details out, or get the group to a vote, thinking that will help. The best outcomes I see are when the group feels it is time to decide. You may be able to help this with timeboxed activities, where you can give gentle reminders of where they should be at, but ultimately the group has to feel they came to the decision through their discussions. With this group, I timeboxed the exploratory exercises into short segments, and had an overall timebox for the session that we agreed on which helped keep the group focused during the more open time periods. While I was fairly stringent on the shorter timeboxes, I was willing to allow the general conversation to go a little longer if needed. At the end, the group decided to do a vote to close – and unanimously voted to do just that.

Dealing with any kind of reflective activity can generate strong emotional responses. It’s up to you as the facilitator to not only guide the group – but to stay out of the emotional whirlwind. By doing that, you can help the group discover the decisions they need to make and allow them the room they need to work through those decisions.