In a recent post, Jim Shore blogs about a “Minimum Viable Hypothesis.”

With MVH, the first step after figuring out the problem to solve isn’t to create a minimum viable product. Instead, the first step is to brainstorm market hypotheses. Which groups have the desire and funds for a solution?

What Jim is blogging about is another side of the minimal coin, and since we teach this in our classes, I thought it would be worth posting about how both sides look.

First, let’s imagine you have The Next Great Idea. Your mind buzzes with all of the uses, and ways it could help people and make money. You literally have a laundry list of the features, and markets. But now you are in one of two positions:

- You are approaching a market where you have to sell a solution to someone’s problem. Of course, as the great Jerry Weinberg says, selling a solution implies that someone has a problem, and people don’t have problems (at least none they’ll admit to you if they didn’t hire you to solve it). Here you are proposing different or better ways of doing things, and quality and feature sets matter.

- You are approaching a market with an actual need or void. Here, time to market matters because if you miss the market opportunity, someone else will fill it.

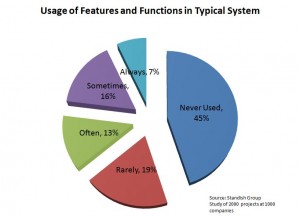

These may sound similar, but there is a key distinction in how we approach the Pareto solution – known as the 80/20 rule (20% of the system provides ~80% of the value). One chart we use shows the results of a Standish Group survey of 2000 projects at 1000 companies detailing the usage of features and functions in a typical system:

A key takeaway we teach our students is that, if you want to go faster, stop doing the 45% of features that are never used. And even if the Standish group numbers are debated – the reaction of my students thinking about their own systems easily validates that we waste a lot of time in the Never Used category.

But, the chart details something else. If we actually know the Always and Sometimes features up front, why would we wait to ship the product to complete the other features?

This, to me, is the key distinction of the Minimal Viable Product. We know the highest value items, so we work to build and ship those first. We then are guided by the feedback (and profits) of the release to incrementally improve the product. And, in my experience, you can only know those items if you are filling an actual need or void.

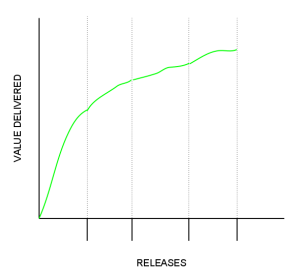

When we do release, it looks something like the chart to the left. We push out a release which gets a ton of value and revenue first, and then use the feedback so that each subsequent release adds incremental value to the product and the customers.

When we do release, it looks something like the chart to the left. We push out a release which gets a ton of value and revenue first, and then use the feedback so that each subsequent release adds incremental value to the product and the customers.

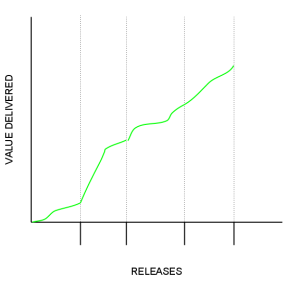

If, instead, you are attempting to fill a perceived need or void, or you think you can do better, then you don’t want to focus on what you think the 80/20 is, because you could easily be wrong – wasting a lot of time and money in the process (as Jim detailed in his post). Instead, what you are looking for is a release which gives you enough information to discover where the market is and what those 80/20 features are. I like Jim’s term of the “Minimal Viable Hypothesis” here, because that is what it is. You are making a guess – a hypothesis – of where the market is, and now you need to run some experiments to see if that’s actually viable – before you build an entire set of theories around it.

So, in a Minimal Viable Hypothesis release, we’d see an initial release with minor adoption and profits, because we are using it as a feedback loop. In fact, I joke with my students and tell them that, in this case, you should purposely deliver what the customer doesn’t want so that a) You are reminded that you are going to have to rebuild it anyway b) You get the feedback loop faster, since you know it’s what they don’t want and c) When you get people fired up, you learn a lot – and people mad at software are pretty fired up!

So, in a Minimal Viable Hypothesis release, we’d see an initial release with minor adoption and profits, because we are using it as a feedback loop. In fact, I joke with my students and tell them that, in this case, you should purposely deliver what the customer doesn’t want so that a) You are reminded that you are going to have to rebuild it anyway b) You get the feedback loop faster, since you know it’s what they don’t want and c) When you get people fired up, you learn a lot – and people mad at software are pretty fired up!

So, thanks Jim for a great label for the other type of release. I think that most people will find themselves solidly in the MVH camp – and that many startups would be very wise to heed the advice to get something to your customers to use as a feedback loop for making what they really want.

Great commentary on this. LeanStartup is a must read!

This is a great article and I always ask this question to software developers. I get mixed answers. What if you decide to build features that customers don’t know they want…yet. And you think you can help them discover that they are wrong.

A lot of people say don’t build features that customers don’t want. But customers might be wrong. They don’t know they want that because it never crossed their mind.